The least connected people in America

Nowhere is the ‘digital divide’ more extreme than on tribal lands. Will Washington’s solution fix the problem?

ROFINO, Idaho — Alexis Coomer’s house isn’t located in a remote area, at least not compared with many of her fellow Nez Perce tribe members on this reservation in north-central Idaho. She lives in the 3,000-person town of Orofino, the go-to place on the reservation where people load up on groceries and other supplies.

But when she needs to type an email, or help her daughter with homework, she drives 6 miles down the road, along the Clearwater River, and pulls into the Teweepuu Community Center, where she works as an administrative and events aide. There, she sits down in front of the computer she uses for work, which has the broadband hookup she lacks at home.

“It’s not that far, but I just hate having to leave my house,” Coomer said. “I’d rather just stay home.”

As broadband internet becomes more and more important in the U.S. — the way Americans do everything from apply for jobs to chatting with their relatives to watching TV — one gap has become more glaring: the difference between those who have broadband and those who don’t. An estimated 24 million people, about 8 percent of Americans, still have no home access to high-speed internet service, defined by the Federal Communications Commission as a download speed of 25 megabits per second. (That’s what the FCC says allows telecommuting or streaming high-definition video.) The overwhelming majority of those people live in rural areas, like farms or in big, poorly served areas like this one.

The shorthand for fixing this problem is “closing the digital divide,” and FCC Chairman Ajit Pai says it’s his top priority. But it has been a high-priority problem for years and remained persistently out of reach for reasons rooted in the structure of our telecommunications system itself. Internet access in the U.S. depends almost entirely on private companies; unlike other crucial services like postal delivery or electric power, it isn’t considered the government’s job, and isn’t regulated as a public utility. But the limits of that system have become painfully apparent: Companies can’t make money by running expensive wires to few customers, and a complex tangle of incentives offered by the government hasn’t solved the problem in towns like Orofino.

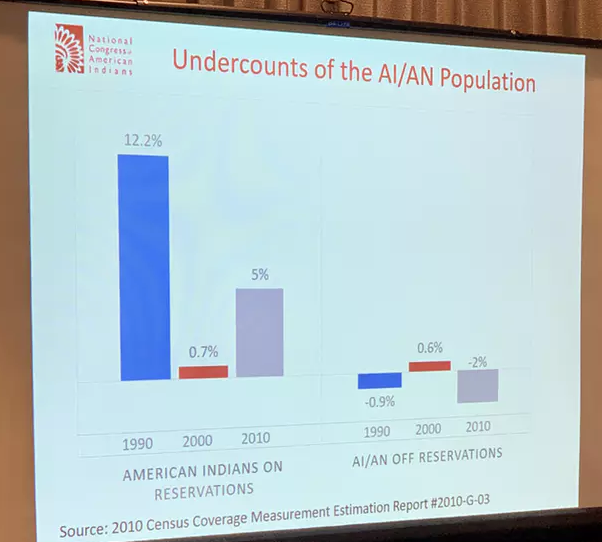

Nowhere is the lack of broadband access more acute than in places like this: Rural Indian reservations have lower rates of coverage than anywhere else in the nation. About 35 percent of Americans living in tribal lands lack broadband access, according to the most recent report by the FCC. In Idaho, the FCC estimates that 83 percent of the tribal population lacks broadband, making the Nez Perce tribe among the least-connected groups in the country.

“It seems like everybody has the internet, but not in my neighborhood,” Coomer said.

The problem has been tackled by three FCC chairmen, by phone and satellite companies, and by the Nez Perce themselves, who launched a bootstrapped internet service in 2010 that currently supplies the libraries and other tribal buildings with a high-speed broadband connection. But service to most houses is still slow and expensive, if it’s available at all. A local cable company offers a 15 Mbps connection for $80 a month, which Coomer says is too slow and unaffordable. Cellphones help fill the gap, but have severe limitations: Data plans are expensive and it’s hard to do homework on a phone.

Around the world, access to high-speed internet is increasingly seen not just as a convenience, but even a kind of human right, the main tool people increasingly rely on to interact with the government, the economy and each other. Yet according to the FCC, more than 30 years after the U.S. government adopted the protocols that became the internet, 8 percent of Americans still can’t connect to it.

If Pai and the FCC are going to find a way to bring quality internet to those Americans, they’re going to have to figure out just how to solve the kind of problems that converge on this tiny salmon-fishing town, where residents look at the world they can see on their patchy connections and wonder if they’ll ever catch up.

“They could be doing some of the programming they have on the computer, advancing on their own, and they can’t,” said Coomer of her four children, who use computers at school, but rely on less-useful smartphone connections when they’re home. “They don’t have the convenience of just getting on the computer and looking something up.”

Rural broadband might not be a headline political issue, but it’s been on and off the Washington policy radar since at least 2010. That’s when the FCC decided to tackle it on a broad scale and issued a National Broadband Plan. The idea was that companies needed a federal boost to make it feasible to serve rural customers.

The plan has several parts including something called the Connect America Fund, which in 2015 awarded $9 billion over six years to 10 telecom companies that agreed to deploy broadband in rural areas across the country. In Idaho, a national telecom provider called CenturyLink is getting $6.3 million a year for six years to expand rural broadband service in the state. Century Link has pledged to bring service to 12,000 state residents; so far, about 500 homes on Nez Perce lands have benefited. A second company, Frontier Communications, is getting $5.2 million per year for six years to connect 10,000 residents in Idaho. But it’s not clear if either company will hit their goals or how much of the reservation will eventually benefit, and at what speed; any connection at least 10 Mbps counts, even though that’s less than the FCC’s own 25 Mbps standard.

What’s more, reservation residents can’t be sure if either company will eventually reach their neighborhoods. Broadband companies have some flexibility to choose which areas make the most sense to connect, so it won’t be clear until the program ends in 2020 just which communities will be left out.

The confusion isn’t helped by the FCC’s broadband maps, which are supposed to show which areas have broadband and which don’t. But the agency acknowledges the maps have limitations. For instance, the FCC maps broadband according to census blocks, and considers a block “served” if a company offers broadband to at least one subscriber in the area, even if their neighbors can’t get it.

The FCC maps show splotches of high-speed broadband available in parts of Orofino, but Coomer’s house is in an area colored blue — meaning there might be some providers in the area, but none that reach the FCC’s benchmark speed. According to the FCC’s 2016 broadband report, 7,793 out of 8,369 residents in Clearwater County, where Orofino is located, lack that kind of broadband access — about 93 percent.

“What you have is a problem where some customers are stranded, so to speak,” said Carol Mattey, a former FCC deputy bureau chief in the Obama administration, who helped develop broadband funding programs. “It’s considered served, even though a pocket of it may not be served.”

THE NEZ PERCE aren’t just waiting for help to arrive from Washington, or from telecom companies: Frustrated by the lack of connection, the tribe has cobbled together its own alternative internet service.

It was originally inspired, of all things, by river otters. River otters are a bellwether for the health of the Clearwater River and the salmon who live in it. The Nez Perce are on a mission to restore the salmon populations in tributaries to the Columbia River, and in 2000, Danae Wilson, manager of the Nez Perce tribe’s information technology department, realized that they needed internet service to do it.

For one, the tribal government needed to be able to communicate with some of the far-flung offices monitoring the rivers. Second, the Nez Perce had received a grant to study the health of river otters, but one of the conditions was that they had to send data back over the internet to be validated.

At the time, the local companies offering internet services charged a fortune for slow connections. Undeterred, Wilson set out to connect the tribal buildings by going for “every single grant you could think of.” Eventually, through grants from the state of Idaho and the Department of Agriculture, the tribe built out its own wireless broadband system using microwave towers, and then connected tribal buildings to it using fiber. Then Wilson realized they could extend that internet service to residents.

The tribe still runs the service, but Wilson is the first to tell you it’s not exactly speedy. Nez Perce Tribe Wireless offers 3 Mbps for $25 a month, 6 Mbps for $45, and 9 Mbps for $65. Even the fastest of these speeds isn’t close to the FCC’s broadband benchmark of 25 Mbps. In nearby Lewiston, a town off the reservation, a cable provider offers service that’s 11 times as fast for less: 100 Mbps for $55 a month.

Most residential customers using the tribe’s service are on the 3 Mbps package, Wilson said. The tribe’s community centers and the public schools use a direct fiber hookup, which is faster.

For many residents, the slow speeds offered by the providers in the area, including sluggish satellite and DSL connections, aren’t worth the cost, so they rely on public Wi-Fi instead. For Ken and Betty Bergman, this means walking several times a day to the tribe’s KIYE radio station in the tiny town of Kamiah and sitting at a picnic table to use the station’s Wi-Fi. Bergman does this to connect to the Idaho state website to file for his unemployment insurance. “It’s really a pain, but you can get it done.” Betty gets on the WiFi to check in with family members in California, including a sick sister.

The Bergmans said they don’t have the money for internet service at home or to pay for a cellular data plan. Wi-Fi is their only internet link to the world outside Kamiah.

“We probably go two to three times a day so I can check messages,” Betty Bergman said. “It’s too cold to sit here, so I go to the house and then come back out here. No matter rain, shine or snow, we come walking in it. I like to keep in touch with my family. This is the way I can keep in contact with my family.”

The tribe’s service has some severe limits that affect home customers. The towers rely on a line-of-sight connection to the end user. Speeds are affected by trees, rock bluffs and an otherwise challenging terrain. A rainy day with fog obscuring the pines along the unforgiving hills means it’s a “slow internet day,” Wilson said. A customer herself, Wilson said her signal shoots over two hills from a tower that’s close to 6 miles away.

“I’m paying for 9 megs, and if I get 5, I’m really lucky,” Wilson said. “To watch streaming media, I will log on and download a movie, and then cook dinner and then we can sit down. It takes time.”

And there are pockets of residents scattered throughout the reservation the tribe’s service can’t reach at all.

One of them is D’Lisa Penney, principal of Lapwai High School, who gets her home internet service from HughesNet, a satellite provider, a sluggish connection that involves a satellite dish and line drilled through the logs of her cabin. It’s better than nothing, but not enough for her to work from home or for her teenage son to take online classes — an important tool for rural residents who want to beef up credentials or take advantage of educational opportunities that otherwise would be out of reach. Penney is fortunate that she has a high-speed connection at work, and she and her son put in long hours at the high school after hours, to take online classes or watch video of a lecture or even open a Google document.

“There are things at school I can do superquick, but at home, it’s a dinosaur,” Penney said.

Her brother, Aaron Penney, runs the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery, which is working to restore the decimated salmon population. The hatchery collects data on the thousands of fish it spawns and tracks, including genetics, scales and length. It has a line-of-sight connection to the tip of one of the tribe’s towers, which means some internet service, but the slow speeds mean the workers can’t just log the data as they collect it. Instead, they need to write it down by hand and slowly upload it into a shared database later.

“I’d like to see high-speed internet capability here,” Aaron Penney said. “It’s been a long time coming, I would say.”

Wilson wants to improve the tribe’s service for the hatcheries — there are four on the reservation — as well as residents who are thwarted by the topography. But that means building new towers, and that takes money the tribe doesn’t have.

“You really feel like you’re leaving people behind,” Wilson said.

As the Nez Perce experience suggests, one of the biggest problems with wiring rural America is that every area has its own collection of issues: A sparsely populated landscape full of ridges and creeks is far harder to wire than an urban apartment building or a cookie-cutter suburb. One-size-fits-all solutions just don’t fit very well.

The FCC chairman says things are changing under his watch. Pai has reworked subsidy programs to redirect funding to rural areas that still lack service and has modernized rules in an effort to encourage companies to invest.

“I think we’re at the dawn of some really great innovations in terms of our stewardship of public funds as well as private sector initiatives,” Pai said in an interview. “We just need more time to let those initiatives blossom and to see how far they go in reducing that percentage of the unserved.”

However slowly, the federal efforts are making some progress at the national level: A report released earlier this month said that in 2016, 35 percent of residents of tribal areas lacked access to broadband, down from 41 percent in 2014. Providers using Connect America subsidies say they have built out broadband connections to 1.5 million locations.

Pai acknowledges the commission’s mapping problem, and said the agency is updating the way it collects information from providers in an attempt to more accurately understand which areas of the country really have broadband. He described it as an ongoing process that is extremely labor-intensive.

He also believes things could improve with a new idea the FCC is trying: a “reverse auction” being held this summer in which providers will compete for subsidies to fund broadband in parts of the country that lack speedy service, including areas on the Nez Perce reservation. The agency plans to award up to $2 billion over the next decade to companies to deploy broadband in areas that aren’t being served through the private sector or by other subsidized companies. (The “reverse” means that companies will compete to offer the lowest bids for the best service.) Pai said the agency took pains to ensure that a range of companies can participate, including some of the country’s rural electric cooperatives, which have expressed interest in adding internet to the electric services they already provide to remote regions. The cooperatives have historically focused on their core business, but see opportunities to add broadband to their services because they are already laying fiber connections for smart grid management, and it’s a service their customers are increasingly demanding.

For the chairman, success will mean that when he travels throughout the country — Pai is fond of road trips to rural areas — residents will have the same ability to use the internet as their urban counterparts. “There’s no numerical threshold, but I have a feeling we’ll know it when we see it,” Pai said.

Mattey understands the frustrations of people who are still waiting for service – she worked on the funding program for seven years — but cautions that it’s too early to be pessimistic. She compared bringing broadband to rural America to the construction of the interstate highway system or rural electrification. “In each case, it took 10 or 20 years to get it completely done,” she said. “It’s unrealistic for people to think it’s going to happen in a year.”

Blair Levin, a former FCC official who worked on the national broadband plan, says policymakers confronting the rural broadband problem need to start thinking of it as an investment in public infrastructure that will yield larger social benefits.

“America is very good at certain things and very bad at certain things,” Levin said. “We’re not so good at investing in the common good… We can see common benefits, but the political forces don’t align to fund them.”

For the tribe’s part, the Nez Perce are planning to compete in the upcoming auction themselves to go after funding to extend broadband to areas, like the hatcheries, that lack access. They don’t feel like they can count on private companies to ever get around to them.

“If we’re not doing it ourselves,” Wilson said, “it just isn’t getting done.”

Authors: Margaret Harding McGill is a technology reporter for POLITICO Pro.

Comments are closed here.